Mesopotamian Tablet Collection

The Museum holds a collection of nearly 1,750 ancient Mesopotamian inscribed clay tablets. They were purchased for the Museum between 1913 and 1915 from scholar/antiquities dealer Edgar J. Banks with the support of University President Edmund James.

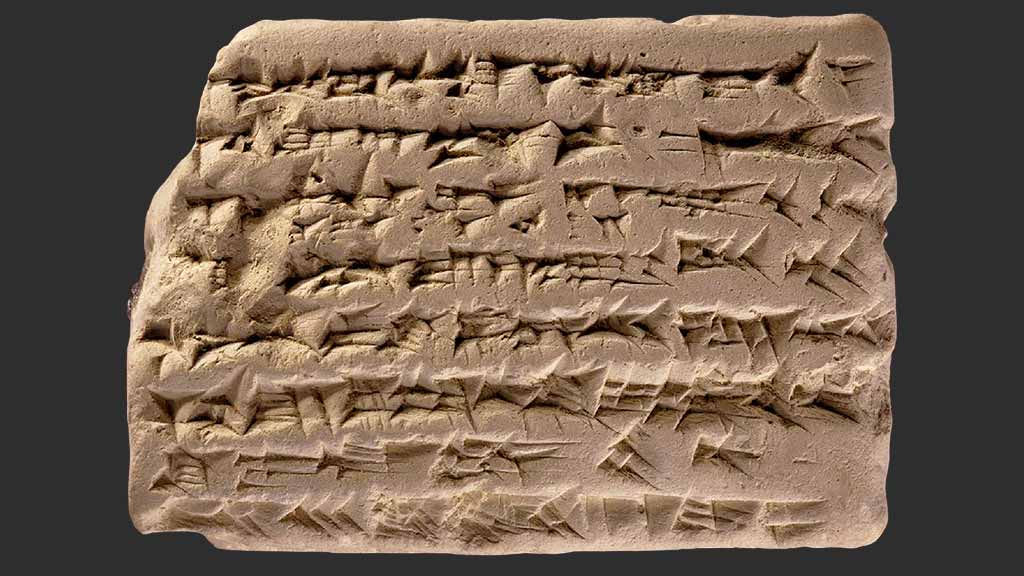

The tablets are written in two ancient languages, Sumerian and Akkadian, using a script called cuneiform. Cuneiform is the earliest writing system in the world and was made by impressing triangular-shaped wedges into wet clay tablets. They offer a fascinating glimpse into the daily lives of people who lived thousands of years ago. The tablets can be divided into three groups by time period:

Third Dynasty of Ur

About 1,100 of the tablets date from the period of the Third Dynasty of Ur, (ca. 2112–2004 BCE). They were discovered in the administrative archives of 2 towns in southern Mesopotamia, Umma and Puzrish-Dagan. Many of the tablets detail the arrival of livestock received from individuals (early taxation), which were distributed to members the royal court, to temples for sacrifice, or to the army for food. Other tablets describe the dispatch of teams of workers (both male and female), food rations to government officials, the distribution of garments, instructions for making bronze, the transfer of large numbers of reed bundles, and other administrative matters.

-

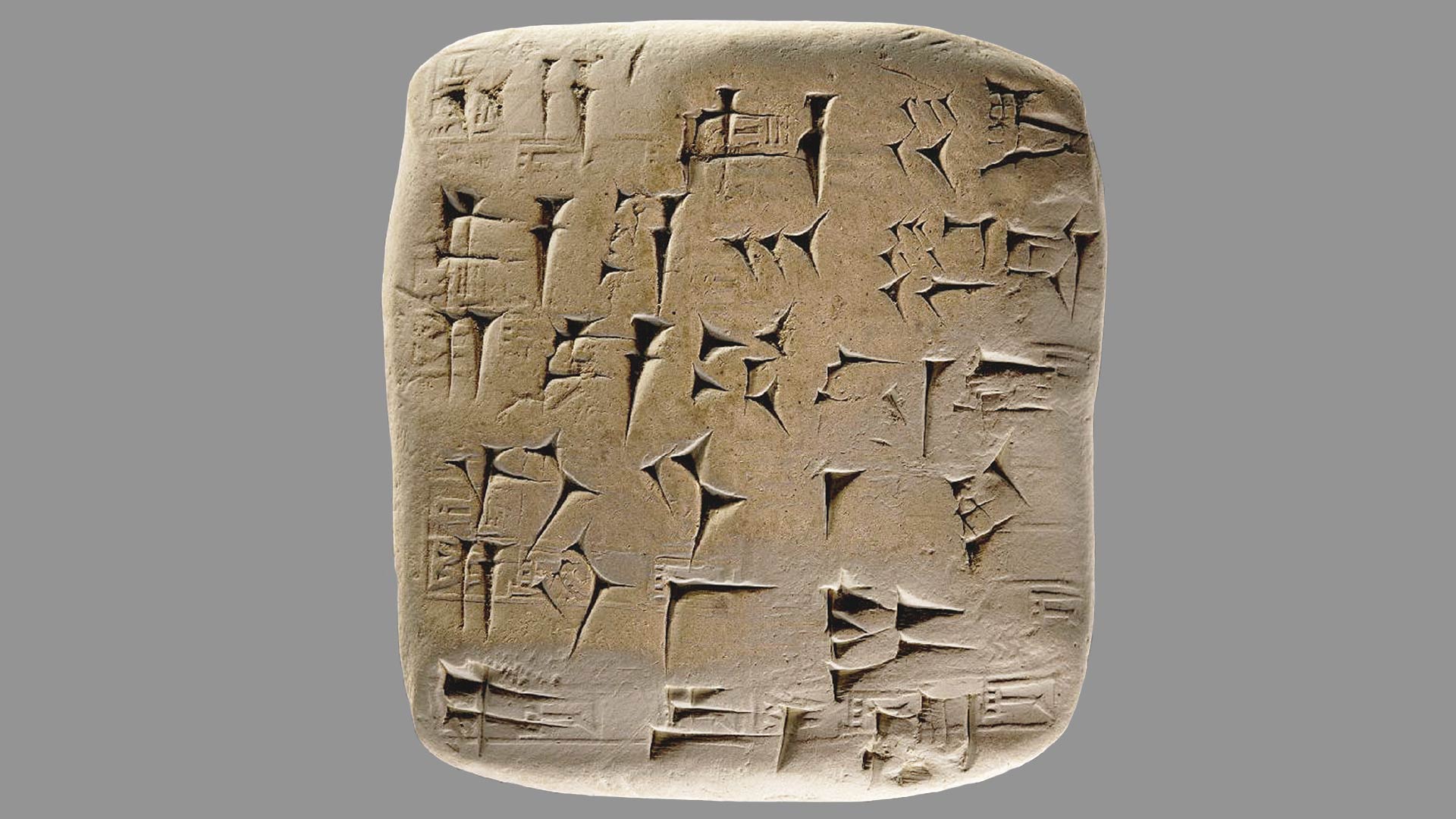

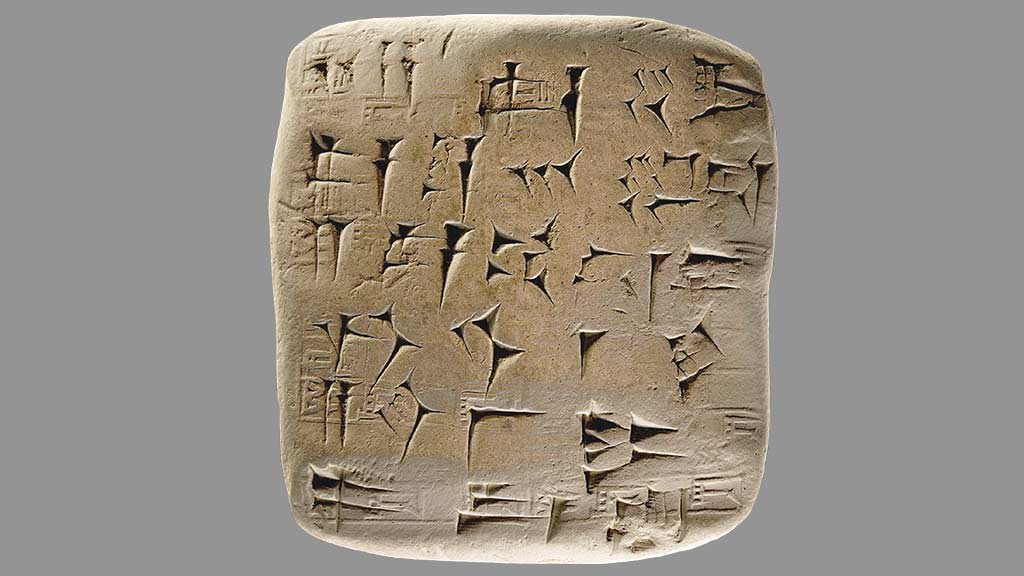

List of Men Working at Barley Harvest Umma, Sumer, modern Iraq 5th year of King Amar-sin, ca 2041 BCE Ur III Period (2112–2004 BCE) 1913.14.0550

List of Men Working at Barley Harvest Umma, Sumer, modern Iraq 5th year of King Amar-sin, ca 2041 BCE Ur III Period (2112–2004 BCE) 1913.14.0550

Old Babylonian Period

About 400 tablets date to the Old Babylonian Period (ca. 2000–1595 BCE) . They appear to have come mostly from the city of Uruk. Besides a large number of administrative tablets, there are some literary texts, including a fragment of a Sumerian epic featuring King Gilgamesh of Uruk, several royal inscriptions, and a notable medical incantation.

-

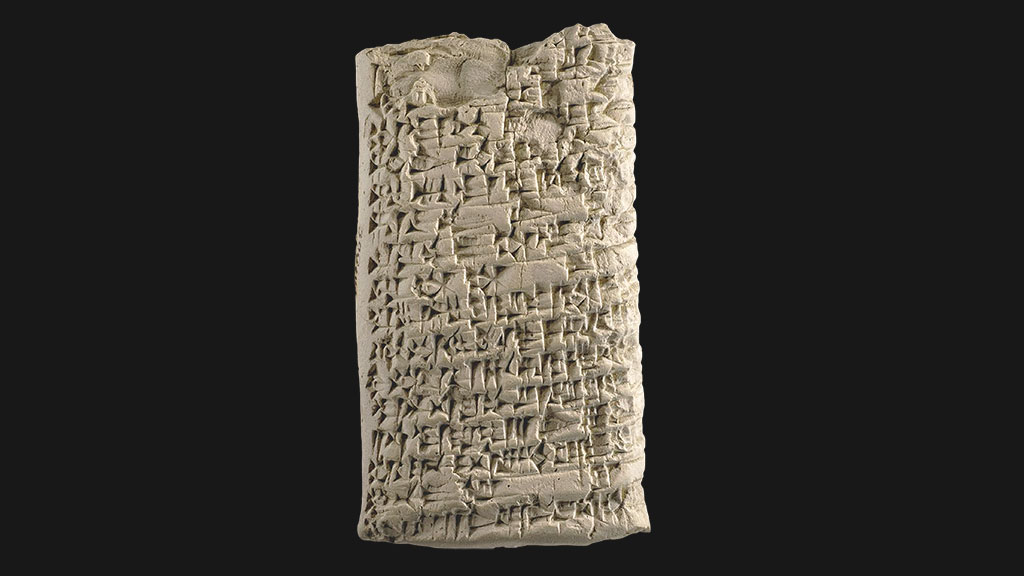

Incantation Against Several Diseases Babylonia, modern Iraq Old Babylonia Period (1792–1595 BCE) 1913.14.1465

Incantation Against Several Diseases Babylonia, modern Iraq Old Babylonia Period (1792–1595 BCE) 1913.14.1465

Neo-Babylonian and early Persian Periods

The collection also contains about 250 texts from the Neo-Babylonian and early Persian Periods (ca. 625–522 BCE). These were also found in the city of Uruk. They come specifically from the archives of a great temple called Eanna, dedicated to Ishtar, the goddess of love and war. Most of them are administrative receipts for goods coming in and out of the temple, as well as promissory notes concerning the farmers who worked the lands that belonged to the temple.

-

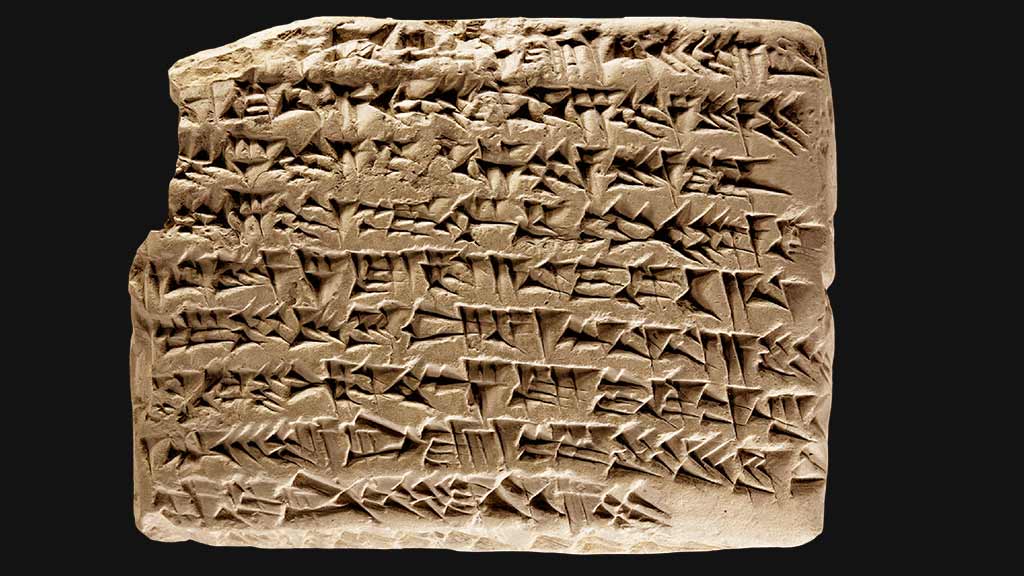

Boat Rental Receipt Uruk, Babylonia, modern Iraq 540 BCE, 15th year of King Nabu-Na'id's reign Neo-Babylonian Period (606–539 BCE) 1913.14.1652

Boat Rental Receipt Uruk, Babylonia, modern Iraq 540 BCE, 15th year of King Nabu-Na'id's reign Neo-Babylonian Period (606–539 BCE) 1913.14.1652 -

A Summons to Give Testimony in Court Concerning 30 Sheep of Disputed Ownership Uruk, Babylonia, modern Iraq 591 BCE, 14th year of King Nebuchadrezzar II's reign Neo-Babylonian Period (606–539 BCE) 1913.14.1706

A Summons to Give Testimony in Court Concerning 30 Sheep of Disputed Ownership Uruk, Babylonia, modern Iraq 591 BCE, 14th year of King Nebuchadrezzar II's reign Neo-Babylonian Period (606–539 BCE) 1913.14.1706